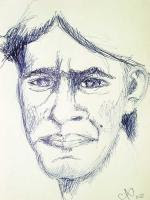

An ode to my good friend Francisco Christich, this was the most personal piece I've ever been assigned. He's talented, intelligent, and forced to clean bathrooms of a bar...

For the original illustrated story visit:

www.tsweekly.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=3112&Itemid=2

We met at the Westside Tavern last December, a stool between us and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off on the TV. Pointing to the screen he sighed, “The downturn of society...” I, however, considered John Travolta a sign of the Apocalypse, underscored by his contribution to Hairspray. Two beers and all of Francisco’s money later, now seated side by side, we both agreed that the tipping point of America was Ronald Reagan.

Francisco Christich: the name of a friar or cult leader. Or an artist, nine-ball guru, father and friend. Francisco, the most modest human being I met in my nine months in Central Oregon. A song; the antidote to gloating galleries and braggart collectors, trust-fund artist managers – We both knew we’d spend much time together after that night at the Westside. Yet neither could have guessed how rotten it would end.

His entry to Bend was apt. It was a choice between here or Sante Fe; “When the car broke down that kind of made the solution clear.” That was 30 years ago. Francisco will be 62 in September and shows every second on this Earth. A scar under his gray hay hair from a car crash 20 years since (of windshields he offers, “They’re hard – they win, you lose.”), ashy marks like cuffs around his wrists (“Some pigmentosis...” he explains, then jokes, “Actually I got those storming the cliffs of Normandy.”) and a silky white beard Santa would wear if evicted from the North Pole. An American mutt, Francisco’s father was Mexican and Slavic while his mother was Native American and French, “As far as I know.” Raised in East LA, it was his mother who sat him down at an easel when he was four and told him to paint.

Fifteen hundred works later, Francisco Christich is a famously unknown artist. Some of his paintings hang on private walls (mine included, bearing his sublime “Cosmic Junkyard”), 500 are in storage while the other 1,000 “just slipped away.” Of the three total murals in Taos, New Mexico, he painted two. In Bend his works are scattered across town, the most recent being outside the Wall Street Bar – three panels depicting a ghost town along Smith Rock, Klondike Kate, and a tall two-section piece showing the flow of the Deschutes. The images are striking, more so because Francisco hardly had any paint, “Green, blue, had to steal some red – It was fun, challenging to use exactly what I had.”

He’s being charitable today. The last time I saw Francisco he wasn’t so merry, rather bitter. A room for rent has made all the difference. Francisco’s been homeless for the past few months, hopping between couches and empty buildings. “You can only stay in a place so long, you gotta keep moving...” Nearly arrested on the westside for squatting weeks ago, he overheard a conversation between the building’s owner and leaser and knew then the jig was up. Onto another place, this is nothing new; “I lived on the street in the ‘90s.”

To know Francisco, look into his eyes. Talk to him. Buy him a beer for the effort; honor. The miracle of this man is his undeniable aura, however dire the situation or dour his spirit. For an artist to watch the rise of Bend as an artistic city, and to be ignored throughout, he has every right to feel slighted. But it runs deeper, and why Francisco deserves recognition – Because he seeks none. Instead of jealousy or angst he takes a long-view, ever the outsider, “I saw in the local arts magazine all the people at Art Walk smiling, drinking wine. That looks like fun.”

Francisco doesn’t do shows. He had one in Tacoma and describes it as “a lesson in futility.” He’s shy at first then affable and gregarious after proving you’re a “real human being” – I had a ping pong party in January and, of the nearly 20 contestants, Francisco was the only one who didn’t play. But he was the one person everyone remembered, with some offering him a room if he’s ever in Portland.

I was renting Val and Tyler Winterholler’s home in Tumalo at the time. Val’s an artist too, a painter with a sense for scratching a seemingly finished piece to reveal its true soul. Inexplicably she started painting pods nearly two years ago, until realizing she was pregnant with a daughter, Tessa – a subliminal if not eerie signal. Alas, their house was soon for sale so I moved an alley away, into an overpriced shack with bad vibes. I couldn’t create, winter wouldn’t go away, and I wasn’t the only one struggling.

Francisco had lost his studio apartment in the Broadway Courts, unable to afford $450 a month, and his landlords refusing to take art in lieu of rent. “Nice people, sorry I lost it.” Back to hopping couches, again, and his constitution worsening – wheezing and tearing, allergic to the dog in the house. It’s hard to bitch when bumming a bed, but Francisco obviously needed help. So I took him in, offering a spare bedroom with visions of an artistic commune: Me writing, him painting, quitting late afternoon to molt minds.

Gentle, passive, introspective, Francisco is a flower child with caveats. Speaking of his generation he gets sentimental, “We’ve been through peaks and valleys, and now we’re in a valley... The Sixties were quite energetic, dynamic, the age of assassinations, LSD. There are two hippie generations, one on TV and the other real. I think that story’s never been told, the revolution. We bought a bag of goods, a picture of a picture of a picture.”

It’s such introspection and modesty – Francisco’s inability and/or unwillingness to go out and sell himself – that has limited his success, as he readily admits, “I’m always open to offers but offers are few and far between... If you don’t compete it’s a little tougher.”

Instead of competing and promoting, Francisco creates. He paints, incessantly, two or three projects at a time. Early inspirations being Gauguin, Cezanne, Dali, Picasso (“The beginning of the end of art – The traditionalists hated those guys”) now his art emerges from his mind, “I suppose dreams, and Native America, to keep it alive.”

Francisco slowly recovered but was ever sensitive to my smoke (cigarette at least), buying us groceries with his food stamps, seeking inspiration. It lasted hardly three weeks. That house is cursed and I simply had to leave, find another spot. Our farewell was in the form of a yell, “See ya, Francisco!” mopping the floors of our failed commune as he pushed his bike with a busted front rim away.

I found a house with a dog to sit but he wasn’t so lucky. That’s when Francisco became homeless, again, mostly my fault but the misguided guilt trip that ensued was equally shared. We saw each other but seldom spoke. For a time I considered contacting his son Eli, a writer and graphic artist in Portland, or daughter Hesper Moon, the mother of Francisco’s two grandchildren, and asking them to come and fetch their father. He was in bad shape, mentally and physically. But I know Francisco; his character refutes aid – Even when totally broke I never saw him beg. Subtle nods and blank stares became our greetings and goodbyes. Both bitter, our brief moment of bliss ending so badly, I set to writing as Francisco sought a spot to sleep that night.

Exacerbating the silent tension was the lack of any response from my literary agent. I’d set myself up, see, and dragged Francisco along, dreams and dreads included. “A Strange September Song” is the novel Francisco wrote years ago in a single month. “Like a gift dictated to me. 99.5% the way it was,” is the way he describes the story, the process. About a reckoning between pool hustlers, “A Strange September Song” is based on Francisco’s past life as a nine-ball player.

Not a hustler or shark, rather an itinerant pro since graduating Palo Alto High School in 1964, Francisco’s fame-claim is beating the #9 player in the world when he took Billy Johnson for $35 in San Diego. His “biggest score” was here, pocketing $3,500 total in Bend in the early 1980s, playing $700 a game. And then there’s that Boise bar full of farmers betting. He entered and decided, “It’s not a good idea to hustle a farmer. So I announced myself...” Later, each farmer shook his hand as Francisco left with $500 in winnings. The circuit can be unkind, though, hustlers wear out their welcome quickly: A good friend of Francisco’s, Jesse James (his actual name), took a girlfriend down south, through Oklahoma, “and he never made it out.” Only the girlfriend returned, and wouldn’t speak of what happened to Jesse James.

Francisco doesn’t play much pool anymore. He wins when he does, but fading eyesight and lackluster local competition make it a tedious task. Having been around the best for decades he says of Bend, “It’s like watching Tiger Woods, then going and playing miniature golf.”

“A Strange September Song” is a damn good read if you ask me. But my agent wouldn’t know – I sent her the first few chapters and there’s been no response, yet. This irked Francisco, more so when on the street with no address to receive even a rejection letter. It irked me too, but for other reasons. I had a novel of my own to finish and at last living in a fertile house – If my agent can’t be bothered to read a novel from a friend, will she bother to sell mine? This is when Francisco gets prickly, bringing up the topic of his novel and my agent’s unresponsiveness – Blunt as it may be, I couldn’t be bothered; I’d given Francisco a place to stay, however briefly, and now I had bigger worries.

The bitterness only grew. Especially when I told Francisco I was house- and dog-sitting for Midda and David Kinker on Delaware. Midda is a gem, the nurse I’ll need someday soon, while David is an artist. And competition for Francisco, a fellow muralist, despite the fact he refuses to compete. David is his opposite. A working artist, well-known and in demand, not shy to offer his services for pay, trade (receiving enough coffee for an Army from Strictly Organic to paint an ivy pergola above the self-service area) and at times gratis at public events – “Balloons Over Bend” and the Country Fair.

However inverse, when asked which local artists he respects, Francisco affords, “There’s a lady in Sisters, and I like most of David Kinker’s work.”

And then there’s the new breed, the “corporate muralists” – those who offer to do work for “free” while including product- and logo-placement in pieces. “Undermining the art world,” groans Francisco, “One comes by and offers to do it for free, while a working artist should be charging $20,000.”

Having lived with three artists by now – Val Winterholler, Francisco, and now David Kinker – I’d seen the full spectrum of arts in Bend. But not Francisco for a time, weeks without a glimpse; only by visiting the Wall Street Bar at dawn is that assured.

For money Francisco cleans the Wall Street every morning, his latest mural on the wall outside as he mops and readies the lavatories for another ruckus. “It’s amazing the amount of shit that’s left at the Wall Street – I found a joker’s hat last week, and a used extra large [maxi-pad] lying on the floor... That was nice. It’s amazing what people will do under the influence of alcohol. The nicest people too, absolutely Jekyll and Hyde, but also lots of Hydes and Hydes, it just makes it worse.”

Our final meeting meant closure for both of us. I was on a plane the next week back to New York and he’d just found a room to rent. The bitterness had faded, helped by his new home and several beers. And our conversation, the interview for this article requested by the publisher of The Source (the most consistent patron of Francisco’s work over the years), offered us an excuse to reunite. Never enemies – even as our relationship became strained under the weight of expectation and disappointment – perhaps it’s our shared experience that makes us true friends. Since first meeting at the Westside last December and agreeing that Reagan was the “downturn of society,” living and failing together, then meeting again in mid-July, it’s good to be with an old friend.

To see Francisco smile... To hear him mention “A Matter of Urgency” – his next book which, despite its title, “will take me 35 years to write. It’s a commitment to write and I become obsessive about projects.”

To be graced by his aura: artist, author, nine-ball guru, father and friend.

Survivor: “I have a love-hate relationship with Bend. There is a thriving culture in Bend. Socially it seems only bars; we sold the nightlife but they’ll get out of it. Businesses coming and going. Cookie cutter restaurants in a kit.”

Take a swig my dear friend.

“Buddhists say life is suffering. But it is grand. The universe is a trip, this endless sky.”

Smile.

He sketched me after the interview. Made me appear leaner, more serious, better than I ever could be. So we shook hands and parted ways, no more words needed.

Saturday, August 16, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment